Research

Below you’ll find a brief snapshot of my current and past projects, including collaborative work with colleagues near and far.

How do agricultural and microclimate heterogeneity drive insect occurrence and behavior?

Postdoctoral Research | University of Wisconsin-Madison

Advances in technology are rapidly changing the way that we as ecologists do our science. Innovative new techniques are allowing us collect troves of data to address complex interactions between a rapidly changing planet and the small critters that help run the show. For instance camera traps, a long-time staple of wildlife research, are a new tool in the quiver of insect ecologists as modifications have allowed them to capture much more detailed interactions between insects, plants, and the environment. By capturing images with remote cameras, we can collect data at scales of time and space that were previously untenable - all while controlling some of the biases inherent to human observers.

In this new endeavour, I’m working in tandem with folks at UW to understand how interacting global change drivers, including climate change and agricutural practices, impact insect behavior and occurrence. To do this, I’ll also be helping develop and test new technologies to monitor insects in the field using remote cameras and computer vision methods.

Can bees take the heat? Exploring bumble bee responses to extreme heat in a changing climate

USDA NIFA Postdoctoral Research | University of California Davis

If there’s anything the past few years have shown us, it’s that the impacts of climate change are playing out now. We’ve experienced record heat this year on top of several seasons of other extreme weather events. For temperate-adapted species like bumble bees, how might these new norms of higher average temperatures and an increasing frequency, duration, and intensity of heat waves play out?

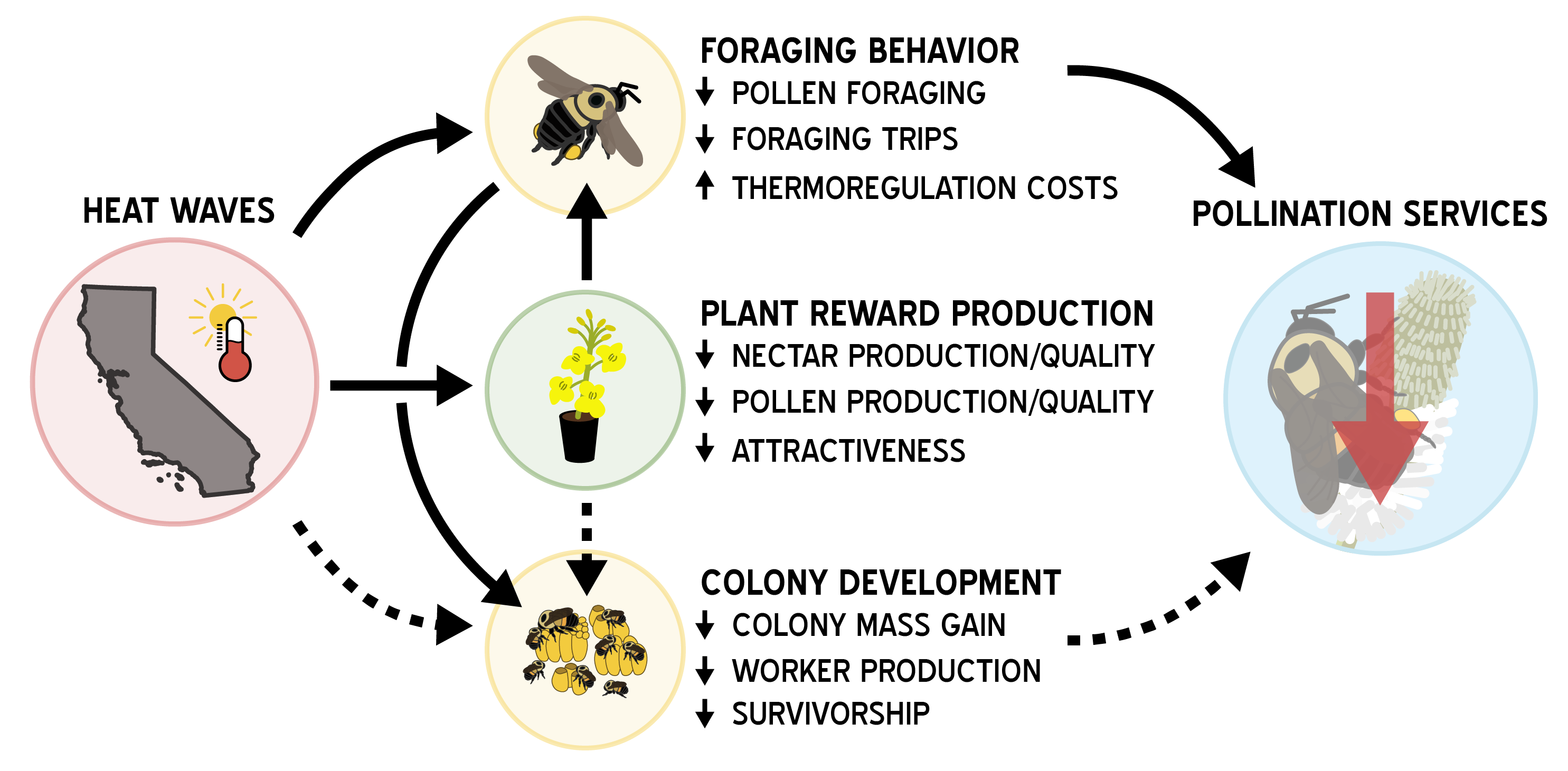

Most animals have a temperature limit above which they start to struggle. For fur-coat cladden bumble bees, a unique group invertebrates that actually do have control over their body temperature (via shivering and heat “shedding”), heat waves may pose a distinct threat of having temperatures far exceed bumble bees’ operational temperature threshold. In such cases, bumble bees may stop foraging for food while they await the temperature to decrease or struggle to maintain an ideal temperature in their nests. For heatwaves that last for several days, this could mean bumble bees are unable to acquire the pollen and nectar required to sustain their colony, resulting in negative effects on colony development and reproduction. Additionally, heat waves during critical windows (such as crop bloom) might result in a decrease in visitation to crops, threatening pollination services and crop yields.

Hypothesized impact of the increasing frequency, duration, and intensity of heat waves on plant rewards and bumble bees and the ecological services they provide.

To address this, I explored the impacts of extreme temperatures on bumble bee foraging activity and behavior using experimental simulations and observational field work. I’ve also worked on large-scale analyses to determine how long-term and recent warming have impacted continental-scale bumble bee commuity composition. Together, these pieces are helping us build a better understanding of how our changing climate might impact this important group of insects.

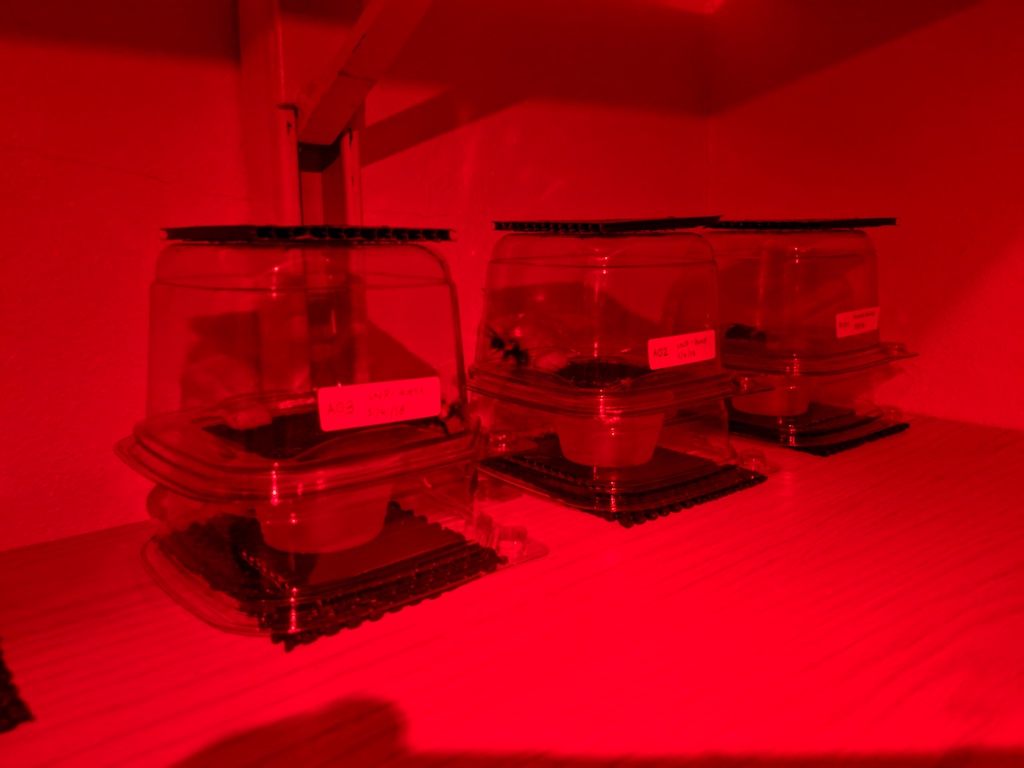

Colleague Nick Rosenberger and I setting up experimental trials in chambers that simulate heat wave conditions for foraging bumble bees and their food plants.

The results of this project will hopefully assist agricultural stakeholders to prepare for worsening extreme weather events by broadening our understanding of how extreme temperatures impact bee foraging and pollination efficacy.

Why are some midwestern bumble bees struggling while others thrive?

PhD Dissertation Research | University of Wisconsin-Madison

Recently, a number of high profile studies on the status of bumble bees have sounded alarms among ecologists, entomologists, and the public. These familiar, fluffy critters are not only a harbinger of spring and summer, they are important pollinators of a number of important agricultural crops thanks to their ability to buzz pollinate, visit flowers on cold/wet days (thanks to a warm coat of “fur” which entomologists call “pile”), and other morphological adaptations.

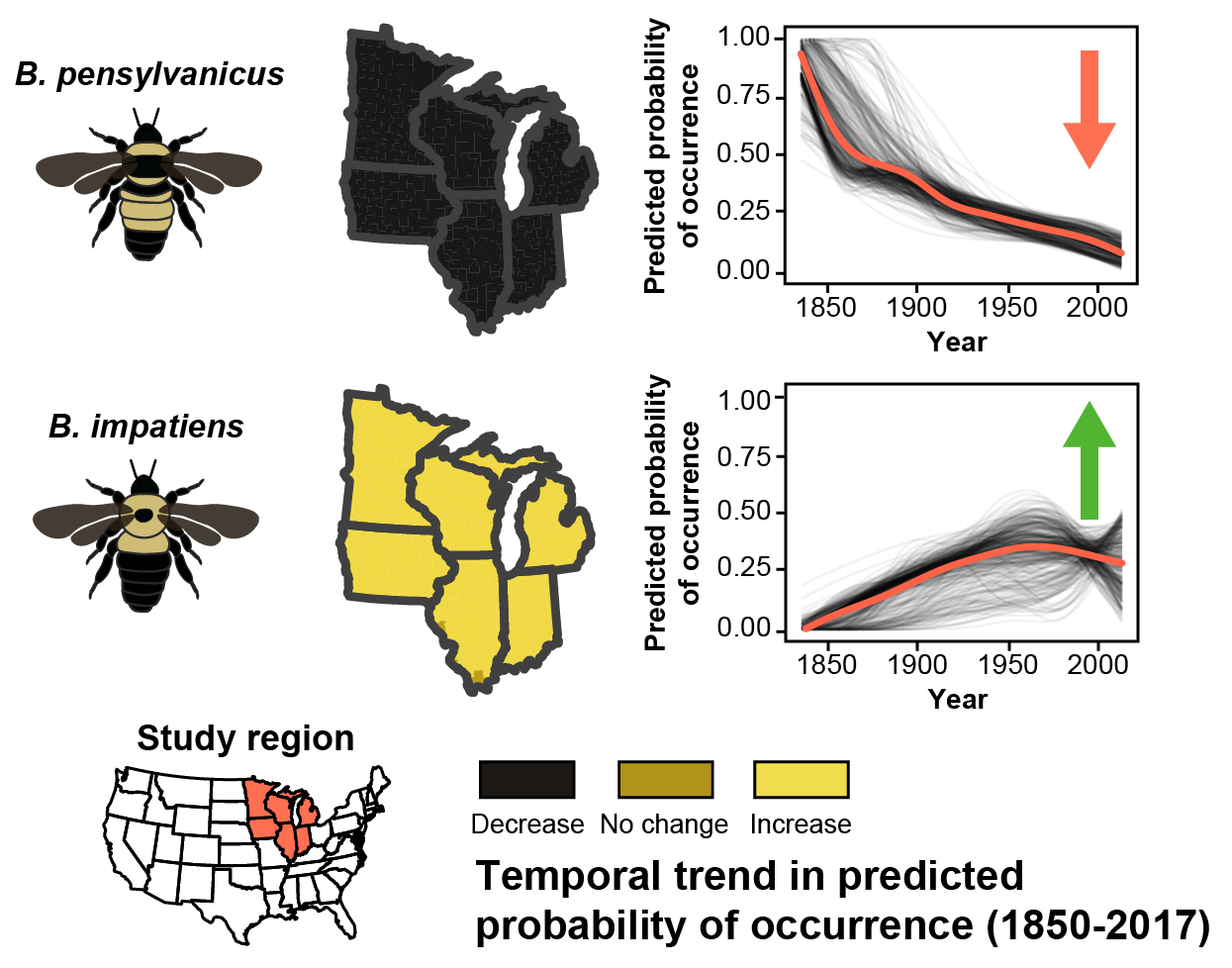

Despite the importance of bumble bees, a number of species declined significantly over the last 50 years. A number of factors have been implicated, including climate change, habitat loss, novel pathogens, and insecticide use. Surprisingly, the same period of time that saw several species populations plummet has seen others increase dramatically. This temporal linkage in species fate, traceable to a period in the mid 20th century, suggests that the same factors might be responsible for the rise of some bumble bee species while others struggle.

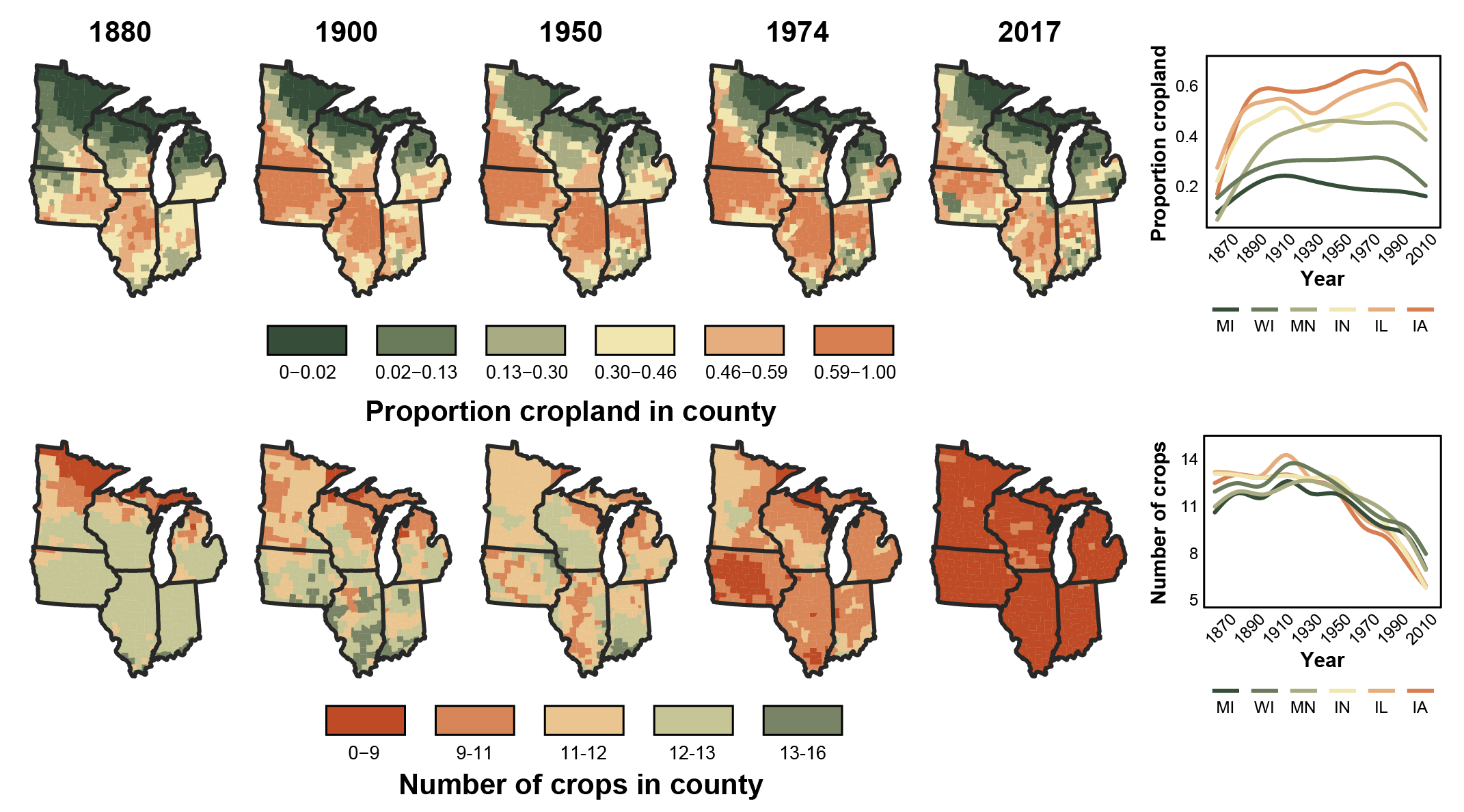

This begs the question: what has changed over the last century that could have led the observed dichotomy of bumble bee population trends? Many studies suggest that as agriculture has taken over as the dominate land-use in the world, bumble bees have lost vital habitat and flowers - the sole source of food for foraging bumble bees. In the place of flower-rich meadows and wetlands, we have planted vast monocultures that only provide pollen and nectar for short periods of time. Because bumble bee colonies are active throughout the spring and summer, they need a consistent supply of pollen and nectar to successfully grow and reproduce. The thought is that some species are better able to adapt to changes in flower abundance in space and time than others, accounting for the differential response of bumble bee species.

The trend in two metrics of agricultural intensity, the proportion of cropland (top) and the number of crops grown (bottom). Over the last century, the amount of cropland has increased, while the number of crops grown has decreased.

This premise was the driving force behind my PhD research. I examined a common, increasing species in the eastern US, the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens), testing hypotheses related to its adaptability to floral resource conditions within modern agricultural landscapes using both laboratory and field experiments. These experiments informed additional field work examining community-level repsonses to resource conditions and a historical analysis linking museum and citizen science observations of bumble bees to agricultural practices to determine whether an increase in the intensity of agricultural practices over the last two centuries could explain both the rise of species like B. impatiens and the decline of others such as B. terricola.

An illustration of the two distinct patterns of bumble bee response to agricultural intensification in the Midwest. In this example, B. pensylvanicus is predicted to be less likely to occur over time given patterns of agricultural intensification, whereas B. impatiens is expected to more likely to occur. The temporal trend figures on the right are county-level predictions from 1870-2017 (thin black lines), along with the overall species trend (red line) fit from long-term models.

Bumble bees collected in a large-scale effort to document the occurrence and relative abundance of bumble bees in Central Wisconsin agriculultural landscapes

Stellar field assistant Grant Witynski checks on a bumble bee colony during a large-scale field experiment testing how temporal resource availability impacts bumble bee foraging and colony growth and reproduction. Arlington Experimental Research Farm

A worker brown belted bumble bee (Bombus griseocollis) forages on purple tansy (Phacelia tanacetifolia) flowers planted to test the impact of temporal resource avaialbility on bumble bee colony development.

Wild-caught queens of the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) inside my Macgyvered rearing cooler. These queens are in the process of laying eggs and establishing colonies.